all strategy requires understanding the bigger narrative

Archived Insights

Insights shared

December 2022

The last year has seen a seismic shift in the ESG and climate landscape. Regulators are upping the ante on everything from greenwashing to stricter climate target disclosures, while the war in Ukraine, disruptions in the energy market, rising interest rates and soaring inflation have all combined to produce a global cost-of-living crisis and renewed geopolitical and macro uncertainty. Add to the mix a spate of climate-induced disasters and the increased politicization of ESG investing, and it’s easy to see why investors have tended to tread cautiously as they seek to understand companies’ challenges and opportunities.

Insights shared

November 2022

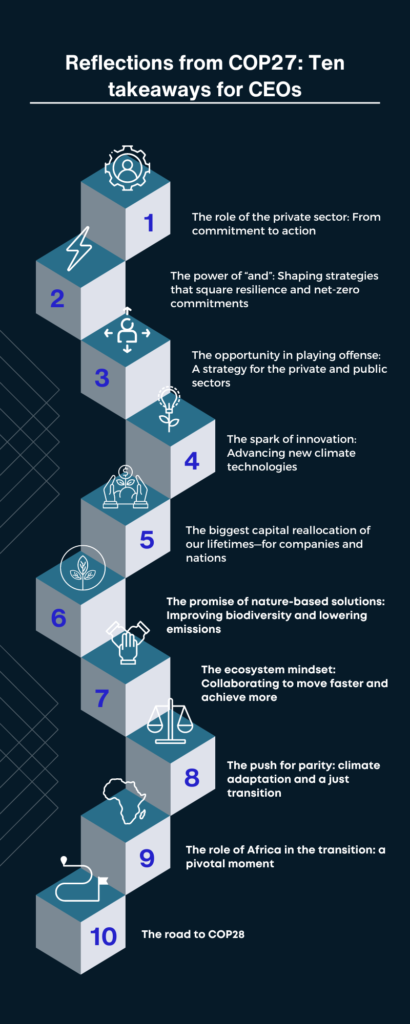

Last year in Glasgow at COP26, we outlined the nine requirements for a more orderly transition, which highlighted the complexities—fraught with challenges and also opportunities—of solving the net-zero equation. With the conclusion of COP27 in Sharm El-Sheik, Egypt, we are reminded that while the annual UN climate gathering is a predictable event—the path to net zero is anything but. The transition was never going to be easy, and recent headwinds such as surging inflation, rising energy costs, and an ongoing war in Europe have brought greater challenges to the journey.

Insights shared

October 2022

“We should try to regulate ESG ratings to try to get much more commonality because they’re very important—they’re being used a lot—but there’s also so much confusion. And we’ve seen that debate, where certain oil and gas stocks are in a rating, and certain stocks like Tesla are out. Not saying one is right or wrong, but the methodology is being confused.”

FCA’s ESG director Sacha Sadan

Excerpts from The SustainAbility Institute by ERM

01

ESG Ratings Are Expensive and Bothersome

A recent ERM research study found that 33 institutional investors spent an average of US$487,000 per year on external ESG ratings, data, and consultants. Those higher operating costs generally get passed on to sustainable investment product customers in the form of higher management fees, which may impact investor returns rather than the bottom lines of asset managers.

02

ESG Ratings Contradict Each Other

Each ESG rater uses its own methodologies to collect and analyse data and to produce scores – methodologies which are often quite secretive. There is little impetus for ESG rating firms—who compete against one another for market share—to try to produce more interchangeable scores or to adopt a unified approach to ratings methodologies.

03

ESG Rating Divergence Is Often Intentional

The divergence described comes about both unintentionally and intentionally. Unintentional divergence is mostly at the level of specific factors or datapoints. If different raters assessing a given company encounter variations in data access or interpretation that lead to contradictory verdicts for one or more sustainability factor, unintentional divergence of ratings is the result. Intentional divergence is mostly at the composite score level and is a product of the sum of a company’s sustainability data—this divergence is the “secret sauce” that distinguishes raters from one another.

04

ESG Ratings Are Not Evenly Distributed

ESG ratings are not equally accessible to investors or to corporations. Nonpublic companies are often left out of ESG ratings entirely. Companies that have recently gone public are unlikely to be rated during their first year of listing. Companies trading on major exchanges in North America and Europe are far more likely to get properly rated than those trading elsewhere, especially in emerging markets. And even within the ranks of stocks listed on major exchanges, companies with a higher market cap or free float get covered by more raters and have their ratings refreshed more frequently than other companies.

05

ESG Ratings Are Not Predictive

ESG risk is not as straightforward as credit risk. Even the definition of success regarding the determination of ESG risk may be in the eye of the beholder. Counterintuitively, improving predictiveness may depend both on more accurate and more divergent ratings, allowing investors to compile a risk assessment that is a composite of differing perspectives and informed analyses.

06

ESG Ratings Are Unregulated

ESG raters can expect increased scrutiny of their methodologies as a likely ripple effect due to regulatory developments such as the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission’s upcoming rules to improve transparency on ESG investment practices, the inclusion of ESG rating rules in the European Commission’s Sustainable Finance Strategy and new rules governing corporate ESG disclosure from both regulators and key standards setters.

Insights shared

September 2022

The extremely detrimental impact of fast fashion on the environment is no news. Besides being responsible for nearly 10% of global carbon emissions, the industry is also infamously known for the amount of resources it wastes and the trash it produces. Here are 10 highly concerning statistics about fast fashion waste.

Excerpts from Earth.org

Insights shared

August 2022

Being forward looking in ESG necessarily calls for considering the needs of a range of stakeholders and society more broadly. Anticipating risks and opportunities and considering what value stakeholders have at stake requires continuous, judicious analysis; ESG is a process, not an outcome. The approach of forward-looking companies is marked by four reinforcing parts of mapping, defining, embedding, and engaging.

Insights shared

July 2022

The “S” in environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing moved into the spotlight during the COVID-19 pandemic as companies faced concerns about employee wellbeing and bold calls for action on social inequality.

Excerpts from Reuters

Insights shared

June 2022

Recent pushback on ESG is a sign that it is evolving, with stakeholders taking steps to make ESG efforts more consistently tangible, meaningful and measurable. Calling out misinformed approaches helps make the case for proper design and action. Many business leaders are using the critique of ESG programs to analyze their current approach and rethink their strategies to create more value and impact. Effective leaders take the following seven actions to evolve ESG sophistication.

Excerpts from Willis Towers Watson or WTW

Why the pushback on ESG is good for ESG

Insights shared

May 2022

If you want to deliver on the promise of your ESG and Governance) and sustainability strategy, then change is not just inevitable; it’s vital. And for truly successful ESG and sustainability transformation, you need to define your purpose, then develop the skills, talent, leaders and culture you need to achieve it.

Excerpts from Korn Ferry

To become a sustainable business, you need to do things differently

01

Purpose

Set the tone from the top

Transform your culture

Measure success

02

Governance

Enhance board capability and composition

Adopt governance mechanisms

Align executive pay

03

Leadership and Talent

Hire and keep great people

Reinvent leadership to drive ESG

Close the skills gap

04

Operating Model

Embed ESG commitments into organisational design

Enable your workforce for ESG

Make transformations stick

05

Culture

Shift mindsets at scale

Build an ESG-enabled culture

Engage all stakeholders

Insights shared

April 2022

Many leaders still see an inherent trade-off between choosing a more sustainable future and achieving business growth and profit. They see ESG-related spending — a capital expense to reduce energy use, opting for renewable energy, paying living wages, and so on — as purely cost, not investment. Much of the reason comes down to five big problems with how we make decisions.

Excerpts from Harvard Business review

PROBLEM

SOLUTION

1. The Numbers Hide the Truth About Real Costs

Solution: Price the unpriced.

2. Our Own Biases Trick Us

Solution: Diversify the group making decisions.

3. We Focus on Short-Term Costs and Benefits

Solution: Redefine your tools for investment decisions.

4. We Think About Costs in Silos (Instead of Systems)

Solution: Broaden thinking on value and think in systems.

5. We Miss the Bigger, Existential Costs

Solution: Understand the world’s thresholds and learn to think in net positive terms.

Insights shared

March 2022

The built environment—that is, the cement and construction value chain—accounts for approximately 25 percent of global CO2 emissions. Reaching net zero by 2050 will require the buildings and construction industry to decarbonize three times faster over the next 30 years versus the previous 30. How can the cement and construction industry achieve net zero by 2050? Here are the key takeaways from a roundtable discussion McKinsey hosted at the COP26 Climate Change Conference.

Excerpts from McKinsey

Insights shared

february 2022

Governments and companies are increasingly committing to climate action. Yet significant challenges stand in the way, not least the scale of economic transformation that a net-zero transition would entail and the difficulty of balancing the substantial short-term risks of poorly prepared or uncoordinated action with the longer-term risks of insufficient or delayed action.

Excerpts from McKinsey

01

Universal

Each of the seven major energy and land-use systems contributes substantially to emissions, and every one of these systems will thus need to undergo transformation if the net-zero goal is to be achieved. Reaching net-zero emissions will thus require a universal transformation of the global economy.

02

Significant

The economic transformation needed to achieve the transition to net zero will be significant. The analysis focuses on demand, capital allocation, costs and jobs.

03

Front-loaded

Several aspects of the transition to net zero would be more significant in the early stages of the shift. More broadly, action is needed over the next decade to reduce the buildup of emissions and prevent rising physical risks that might occur in future decades.

04

Uneven

While universal, the economic exposure to the transition will not be uniform across sectors, geographies, and communities and individuals.

05

Exposed to risks

Management of the transition to net zero will substantially influence outcomes, and any net-zero transition scenario including the Net Zero 2050 one used in this research will be exposed to risks.

06

Rich in opportunity

The opportunities for countries, sectors, and companies could be considerable if they are able to tap into growing markets as the world transforms to a net-zero economy.

Insights shared

january 2022

Companies have been responding in increasing numbers to the imperatives set by the 2019 Business Roundtable statement of intent and changing cultural dialogues to adopt ESG strategies, as well as how to translate these goals into practical, measurable, and trackable efforts.

Excerpts from Harvard Business Review

"Our consumers are very sensitive to social and environmental issues. We have actively engaged with them on these issues in the last ten years, and they have become very aware as consumers. They especially ask for information on environmental policies, workers' rights and product safety."

Walter Dondi, Director of Co-op Adriatica, Italy’s largest retailer